Did you know that a 4-5 second interruption of your work increases the amount of errors you are making threefold? But I am getting ahead of myself. Let me rewind.

I became interested in the topic of focus over the last year. It started out with attempts to organize myself better (a recurring theme in my life). This journey led me down a new rabbit hole, which I did not frequent before: the domicile of a hare called focus. As far as rabbits and their holes go: this is a big one. It also contains a plentitude of adjacent cavities to sink your time into. To name a few of those topics: attention, communication, conscientiousness, interruption, flow, performance, sleep - and that is cutting it short. Frankly, I don’t know the scope yet myself.

In that context I recently came across a very interesting paper with the prosaic title: Pardon the Interruption: An Integrative Review and Future Research Agenda for Research on Work Interruptions (Puranik, Koopman, Vough 2019). As the field of attention and focus research is comparatively young, there is still a lot of fundamental work to be done. This paper pertains to the interruptions research field and is aiming to build said fundamentals: as a meta study of about 250 other papers it proposes shared definitions and processes that pull together the sometimes vastly different approaches in the sources. This helps the reader – me – also to get a birds eye view of the field – while providing a plethora of sources to further get lost in.

Disclaimer: This blog is my own reflection and part of my process of synthesizing what I learned. It contains only my own opinions. I am not speaking for anyone else. I also may be wrong. I refer you to the (linked),original paper(s) for your own studies.

What makes interruptions interesting?

I personally don’t like them. Not a fan. The old adage of know thy enemy applies here: to get them under control in my life, my work, I must first understand them properly.

More so: In my profession you rarely work fully alone. Teams of four to twenty’ish people are the common configuration, in my experience. Not having a clear understanding of how interruptions influence your productivity or well-being is a big problem. The question of how to communicate within a team strongly relates to this: finding the right balance between sharing information, helping each other and having sufficient time to get concentrated work done is a tricky task. Arming myself with the data, with the latest understanding will help finding better solutions to organize teams I work with in the future.

Also, I find this topic oddly fascinating – I don’t really need more reason than that.

What are interruptions?

A question you likely would not ask – because it is pretty damn clear what an interruption is: you know it when you see it. However, it turns out that it is not clearly defined – alas not to the extent that everybody studying the phenomenon speaks about the same thing.

When studying anything the question of how to gather relevant data points arises. Consider you are working on something finicky. You are deeply into it, keeping ten threads of thought in your mind (if barely) and you are close to finishing it. Then the phone rings. It’s your boss’s boss calling. You have to pick up and suspend what you are doing. You lose your threads. That finish line you saw earlier may be lost for the day. This is, quite obviously, an interruption. Now consider a slightly different situation: Same build up, finicky task, many threads etc. Then the phone rings again. This time it’s not yours, but from the person next to you. They pick up the phone and start talking. Loudly. Laughing. Gesturing. Annoying. Your concentration is lost. The threads are gone. Another obvious interruption!

However, obvious to whom? Obvious to you, experiencing both of those scenarios? Sure. But not obvious to an observer, a scientist, who measures the effect of interruptions sitting somewhere behind you. Nor is it obvious to an automated system that counts the amount of phone calls, emails or chat messages that you receive to gauge the impact on your productivity. Hence some researchers defined interruption only as things that changed your behavioral performance (you visibly stopped working on a thing) where others included the suspension of your attentional focus (you kept doing a thing, but your mind was pulled away).

Puranik et al propose to do the latter. Their definition is: Work interruptions are unexpected suspension of an ongoing task. This definition intentionally does not specify that the interruptions need to be observable or that it must “happen directly to you”. Both phone cases above fit into it. The task is considered equally suspended, whether only your mind (invisibly) or also your body (visibly) stopped doing it.

By the way, the word unexpected is also important. A planned thing, like a scheduled phone call, does not count as an interruption - even if it disrupts your work. While that may also have an (negative) impact, the field of study here would be about work organization/planning, not work interruptions.

How do you measure the impact of interruptions?

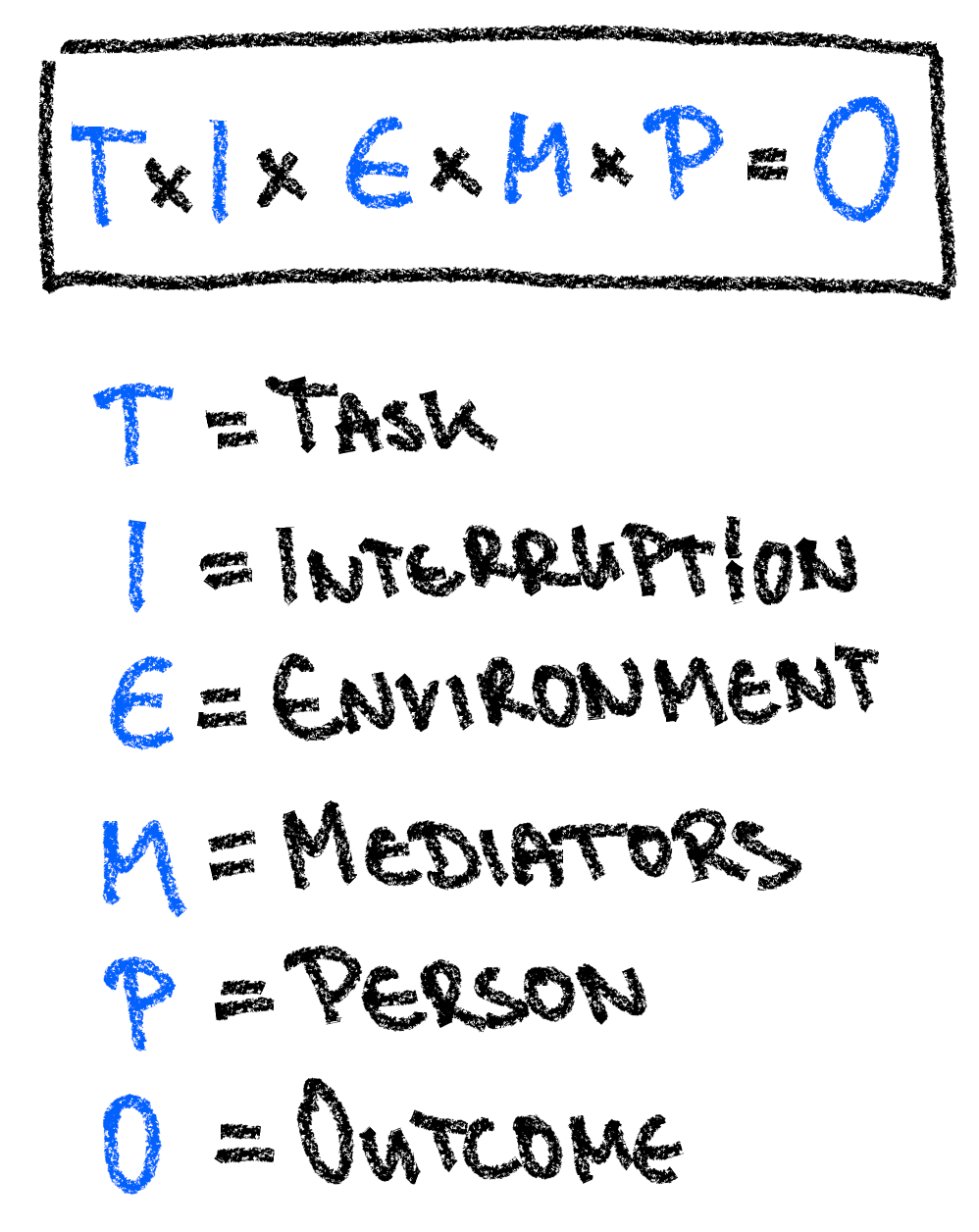

That is of course the big question. The paper makes clear that most studies do not even use the same dimensions or otherwise agree on the same measures. Hence they propose a new model, fetchingly named:

Integrative Process-Based Model of Work Interruptions.

This model comprehensively describes the factors known to this field of research that play a role when speaking about the impact of interruptions. Understanding these factors is the first step to both predict the likely outcome and intentionally mold the outcome. Ath the very least you want to make informed decisions with known trade-offs.

The paper is so well written, that even someone new to the field can easily follow it. However, for my own purposes a complex model is not nimble enough. I need something easier to handle. What I am looking for is more shaped like a formula:

Cost of interruption = A * B + C

Something like that tells me at a glance whether a thing is relevant to the outcome or not – assuming I know what A, B and C are.

The model consists of a large number of details and reasons that lead to the outcome interruptions have. Puranik et al then groups these factors together under shared topics. These topics already come very close to the terms of an equation: this is what I am looking for! Well, not quite, but with a bit of tinkering it will be close enough.

Following I will go through the topics. Or rather: through slightly changed grouping of factors into topics that lends themselves better for my purposes. Later then, I will make each topic a term in my equation.

Here we go:

(T) The Task that is interrupted or is interrupting

This topic is about the thing that is interrupted: The task. Or the tasks.

First, there is the interrupted task, which was going on until now. How complex was it? As in: How much mental energy was bound up in it? How many “threads of thought” were held? How long did it take to “get into” the task in the first place? Also the timing is of importance: Did the interruption occur in between two steps of a long chain of steps? Were these steps independent or building upon each other? Or did the disruption happen in the middle of step? The stage of completion is of course relevant as well. Is the whole thing almost done, or just started? While not in the paper, hence not part of the visited studies, I would also add accessibility, as in an interesting measure: The time and effort it takes to start or restart the task would be multiplied for every interruption.

An interrupting task does not always need to be part of an interruption. Or it may depend on perspective (would you call a conversation that interrupts a task also a task?). Again, complexity plays a big role: how much mental resources does it cost to “load” that new task into working memory? Also similarity to the previous task: is that just a variant of the same, or something entirely different that requires a mental reset of sorts? Lastly, centrality to the “core work” plays a role. Like: is this something that you are normally doing, or something outside of your comfort zone?

(I) The occurring Interruption itself

This topic is concerned with the actual interruption that forced itself into your attention.

What kind of interruption, with what kind of immediacy is it? It can be fully-asynchronous like email or semi-asynchronous like chat or optional synchronous like phone or mandatory synchronous like face to face. At what frequency does the interruption occur? Once in a blue moon? Ten times an hour? Is this an exceptional or a habitual event? How long was the duration of the interruption? 5 seconds? 5 minutes? 5 hours?

(E) The Context or Environment the interruption happens in

This topic is concerned with the external conditions in which the task was executed in and then the interruption occurred in. It speaks somewhat to what extent interruptions can be expected.

Consider the collocation: are we talking open space offices with everyone talking to everyone, or closed offices where people have to knock, or home office? Also the organizational culture plays a huge role: is it a reactive, chaotic, multitasking environment, that expects you often to switch from task to task – or is everything planned out years ahead, with no deviation from the path feasible/needed, everyone knowing exactly what to do? Then the degree of collaboration factors in: is the work mostly done alone, or does it require multiple people forming (temporary) teams and working at it together?

(M) The Mental Factors / Mediators

This topic is about effects that interact with your finite mental resources and your perception of positivity (or negativity).

If you are interested in systems theory, you may find this factor curious, because it seems to convert the whole process into a self-reinforcing feedback loop. This makes the whole system “stateful” and non-deterministic regarding the input.

First, there is the Cognitive Pathway, which pertains to innate abilities and how they “hold up” under the stress caused by the other factors. The memory decay effect works on the suspended task and makes it hard to resume later because your brain clears out the “mental threads” you had in your mind when working on something, when you move on to something else. Also, division of mental resources does not fare well with your hominid brain: it causes conflict, which causes stress, which causes all kinds of nastiness. Interesting tasks that are interrupted also result in attention residue, which means your thoughts keep lingering on the interrupted thing, hence making it harder to do the new thing (not great for either outcome). Last, but not least: prospective memory theory predicts you will forget to get back to the thing that you were doing. Especially when the interruptions keep coming.

Next is the Self-Regulatory Pathway, that is related to motivational or energetic effects. Starting with action regulatory theory, that describes the frustration caused by slow goal progress, which greatly dissuades further progression (example: leaders that are bogged down in mail handling, which is not perceived as making progress, measurably scale down their efforts to, well, lead). Interruptions are principally perceived as goal hampering, hence adding to that frustration. All that, ego depletion theory tells us, empties the limited self-regulatory resources you have, which makes it hard or impossible to deal with other items that require the same resources, like anxiety, that otherwise may have been easily managed. The mental exhaustion ultimately leads to low job satisfaction and is a high-probability pathway to burn-out.

Lastly, there is the Affective Pathway, that is concerned with emotional impact. Simply put: the interrupting thing can be good or bad. Being interrupted by a call that confirms a big client signed up due to previous or ongoing efforts is vastly different from an email from a project manager that adds more items to an already impossible timeline. Also, relevant is the base anxiety level, which has been correlated to the amount and frequency of incoming interruptions.

(P) The Person(s) involved in the Task or the Interruption

This topic deals with people – like you, the person that was interrupted.

We are all individuals. The way we deal with interruptions, stress and multitasking is on a spectrum. Chronemic preferences play a role. A polychronic person does not mind juggling multiple things at once with little stress, whereas a monochronic person is able to focus deeply on a single task. The extent of your ability to screen external stimuli plays a role: do even slight noises pull you out of concentration or can you work next to a jackhammer? Big 5’s conscientiousness is relevant as well. Where others would have given up long ago, someone very diligent can come back again and again to an interrupted task to eventually finish it. The size of your working buffer – the capacity to juggle short term memory – relates to when overload increases the decay speed. Also self-control is necessary to fight off frustration and stay motivated in the face of adversity. Lastly, tenure and experience allow you to be more relaxed in high-stress situations that would thwart someone more junior. What the papers seemingly were not concerned with is neurodiversity. I wonder whether that is a factor.

If the interruption is caused by, or transmitted through, another person, they also play a role in the outcome. While this is not widely researched, it seems at least clear that interruptions from superiors are more distracting than from peers.

(O) The range of measured Outcome

And now finally to the other side of the equation. The paper separates the outcome into two broad domains: well-being and performance. While it is left to the reviewed papers to detail specific results, the measures that are commonly used are introduced.

A simple performance metric is completion time, which directly correlates to productivity: faster completion equals more productive – and vice versa. The task resumption time, that describes the extra time added for picking up a suspended task again, adds on overhead, which increases the total time, lowering productivity. Then there is theerror-rate, that measures the frequency of mistakes when performing a task. This either impacts the quality of the outcome or adds time to fixing those mistakes. The work quality itself is also a measure of performance that is also altered by interruptions.

For well-being there is a range of more subjective metrics, most of which are also impacting performance. For example, job satisfaction is certainly affected by interruptions. A low level of satisfaction results in a different work attitude, than a high one would. Stress is the most common outcome of interruptions that affect planned tasks, as it hinders progression of goals. This goes hand-in-hand with heightened levels of anxiety, which do not help level-headed goal execution either. In the long term stressful interruptions can also cause emotional exhaustion which is strongly correlated with burn-out. Lastly, the paper cites that actual physical distress is not off the table as an outcome.

By the way: All of the performance metrics are directly observable, or at least their effect is. Well-being is not as easy to gauge from the outside and is often measured through self-reporting or interviews or through its indirect impact on performance.

What is the impact of interruptions?

You probably noted the letters that I put in parentheses before each above topic headline. These name the terms of the equation that the model comes down to in my understanding:

Yes, I intentionally ordered the letters so that it forms the Spanish word for time (or weather). Even though I do not speak Spanish (my wife does), it helps me to remember.

I am going to call this a lazy approximation. A simple equation with complex terms. The complexity of each of these terms I layed out above. Chances are the continuous research, that is going on, will add more knowledge and nuance. It likely will change, add or replace many of the factors in the terms. However the topics, aka the terms, may be more stable. The equation itself may hold true for longer.

Either way, the question was what the impact of interruptions is. I cannot tell you, yet - or at least not in any precision. However, having the concept that underlies the model in such an explicit fashion available makes it much easier for me to think about it:

Scoping the outcome

The equation I ultimately want would deal with numbers. I am not there yet. I am far from any meaningful calculation. Before I can think about that, I first need to get a handle on the scope, which will give me the possible range the formula operates in. At least approximate – that is all I need.

Beginning with the outcome (O): Mind, the outcome was separated into well-being and performance. For simplicity’s sake I am not going to differentiate and lump sum everything together as performance. So, what could the possible result here be? That is actually pretty simple. Given an interruption, one of three things could happen: Things get worse, things stay the same or things get better.

Expressing this in numbers I would use positive, decimal numbers (R>=0)):

- Values below 0.0: nonsensical. (Undoing things that were already performed?)

- Value of exactly 0.0: interruptions cause performance to go to zero. Nothing is getting done.

- Value below 1.0: interruptions decrease the performance.

- Value of exactly 1.0: interruptions have no effect whatsoever.

- Value above 1.0: interruptions increase the performance.

Going forward when I write the outcome gets worse then I mean that the performance value is influenced to decrease towards 0.0 – and vice versa for _better _means that the performance value is nudged to increase.

Scoping the terms

To better understand the following, imagine you are looking at a specific role that is offered from a specific organization. I propose that by asking pointed questions you can guesstimate how “interruptive” this role will be and thereby how well you will be able to perform in it – and how your well-being will be impacted. I am not promising that I already have the right questions, but this is fine for now. From what I read so far – they may be close anyway.

Mind also that the terms “worsen” and “improve” will be used in regards to performance – this is not a value judgment. Some functions / roles mandate certain things that cannot be changed. These things have consequences. This is about understanding and predicting these consequences.

Now let’s get to it.

Consider (T) – the Task – and ask: “In this role, how complex are the tasks that need doing and of how many steps do they consist of?” Think of a spectrum. On the left side is written “multiple, very complicated, dependent steps” and on the right side is written “a single trivial step”. Now order the answer you got for that specific role in that specific organization on that spectrum. The closer the answer is to the left, the closer it is to 0.0. The closer the answer is to the right, the closer it is to 1.0. Resulting the value for (T) either worsens (closer to 0.0) or improves (closer to 1.0) the performance.

Next up (I) – the interruption – with the questions: “In this role, how urgent and how frequently do you need to communicate and in what way?”. The spectrum here ranges from the left end (=0.0) “urgent, constant, face-to-face communication” to the right end (=1.0) “pro forma, rare, email communication” . Again, you will find whether (I) for that role worsens or improves the performance in general.

Looking at (E) – the Environment – the question is threefold: “In this role, how do you collaborate, where do you work and on how many concurrent things?”. The spectrum is ranging from the left side “in changing groups in large, open work spaces on many things” to the right side “alone, in isolated space, on a single thing”. Find where the role fits on this spectrum.

Now for **(M) **– the Mediators – is not that easy. Actually, I don’t think that this term has to do with the role or the organization, but only with the individual – and maybe with happenstance. I also think that (M) is not static, but due to change. For example through coaching (and maybe through training) towards improvement – or through workload and stress towards worsening. If that is the case then an organization would be advised to treat this the same way as technical debt: continuously invest into improvement to keep the status quo. However, that is far from a well thought out opinion. Let me get back to you on that (in a follow up article). As an individual, it may help consider the factors that are mentioned (above) and evaluate yourself. If you are scoring low (as in: lower performance) you may want to look for roles that do not additionally worsen performance – especially given that performance also includes well-being!

Lastly comes (P). It has a component that is dependent on the organization: the interrupting person. The question, which likely would not get an honest answer, would be: “Is this role micromanaged?”. Well, if that gets an answer then a “yes” worsens performance whereas an “no” improves it. Other than that, it is again more up to the individual to score themselves – and for organizations to filter for the traits that help them.

Gauging the impact

Now that I walked through all the terms in the equation on both sides, I think there is some immediate practical application: I can now guesstimate what outcome I should expect in terms of well-being and impact on my performance for any role role I come across. At least for three out of five terms in the equation, with the rest mainly pertaining to myself.

I also think any organization should reflect on these terms and truly consider whether their current configuration matches with their goals. I would not be surprised if that is not often the case – especially in the knowledge worker realm, where interruptions seem to be one of the main culprits for productivity loss (getting ahead of myself again).

In any case, I have a much deeper appreciation of the factors that play a role and the questions that I need to ask. While I don’t have any ability to provide specific predictions (like: do X and performance increases by 12%), the landscape of possibilities is much clearer to me.

What comes next?

The error rate of factor three, that I cited in the beginning, comes from a study (Altmann, Trafton, Hambrick 2013) that investigated specifically short interruptions – of three or five seconds in length – that disrupted short tasks (also in the seconds range). There are many more studies, 247 of which are linked in the paper from 2019 that caused this blog article. Many, many more studies came out since then. I just started digging into them and can already foresee that I will not squeeze all my learnings into a single post.

For me, the journey to learn about this topic has just begun. I am already reading a lot of papers and hope to post a new article soon. Most of them are like the one cited above, that is they are concerned with a highly specific experiment. The hard part, well the interesting part, is to accumulate multiple of such studies and find generalizations. In case you are wondering why some engineer is interested in this topic: I think we all should. I think this is a very interesting topic of our time. Also everybody needs a hobby.

One thought regarding the outcome: The paper only classifies the result into performance and well-being. I think a classification of short-term and long-term would be more useful, which mostly would map with the provided categories but would frame it in a perspective that would lend itself better for use (in business etc). Even better would be both (long term / short term performance / well-being).

Stay tuned, next up some more numbers. I am most interested in everything that has a practical consequence. I am glad there is so much material and that others do the leg-work that I can now comfortably consume.

If you want to join a discussion, please visit the cross-published version on LinkedIn.